INTRODUCTION

Dying in an avalanche is probably a horrible way to go. Just prior, you were having the time of your life (literally), and now you are buried under chest-crushing snow, gasping for breath, unable to move an inch while suffering the pain of a shattered leg or some similarly awful trauma. At least it will probably only last about 15 minutes, but that’s a long time to replay the last decision you will ever make, wishing you could go back just a few moments in time to do it differently.

Surviving an avalanche, while significantly better, is likely the same experience right up to that point that your partners finish digging through a ton of snow to clear your airway. Instead of dying, now you only have the nightmare of dealing with your friend who was also caught but didn’t survive. You and your remaining partners decide to leave the body for authorities to recover, and begin the task of getting back to the trailhead with your injuries. Eventually, your focus will turn to the loved ones that your deceased friend left behind, and what you’re going to tell them.

Either way, if you die or if a partner dies, the real burden will be on the survivors. At least the dead only spend a few minutes second guessing that final decision; the surviving friends and family will spend a lifetime. It’s for this reason that you owe it to your loved ones to avoid dying in an avalanche.

The good thing is that avalanches are not mysterious things that come crashing down from above with no warning signs. They require people to trigger them, in the wrong combination of conditions and terrain. With practice, you can learn to recognize the conditions and terrain required, so that you can avoid becoming the trigger.

Although this learning continues for a lifetime, there is a process to follow that can help you reduce your risk even as you gain experience. “Risk management” is this process in general terms, and the SAC Daily Flow describes a risk management process specific to traveling in avalanche terrain.

Risk is defined as “the effect of uncertainty on objectives” (International Organization for Standards: ISO 31000). Given this definition, risk management is the process to reduce uncertainty, to reduce exposure to the effects of uncertainty, and to reduce the consequences of errors. If avalanches, exposure, and consequences were simple things, the risk management process would also be simple, and probably go something like this:

- Reduce uncertainty by digging a snowpit

- Reduce exposure by making a yes/no decision based on the snowpit

- Reduce the consequences of errors by using avalanche safety gear

Unfortunately, it isn’t that simple. Mountain travel, including the people who do it and the environment it’s done in, is incredibly complex and dynamic. Uncertainty about people, conditions, and terrain can be reduced but never eliminated. Your risk management process needs to factor the remaining uncertainties and provide some room for error.

The conundrum is that reducing uncertainty takes practice and learning, which implies mistakes. Yet mistakes in avalanche terrain can have very serious consequences. You need to create conservative enough safety margins to practice and learn without getting killed while doing it. And as you learn, be cautious that your level of confidence doesn’t outpace your competence.

Although your risk management process needs to be more robust than just digging holes in the snow and using safety gear, it also doesn’t need to be burdensome. When applied well, the “Daily Flow” is an elegant way to structure your day. It allows for fun on the snow while reducing uncertainty, reducing exposure, and reducing the consequences of errors. It also provides opportunities for lifelong learning. The following is a summary:

- Consider Your Partners: Consider the qualities of your partners as they relate to risk; including both avalanche and non-avalanche risk.

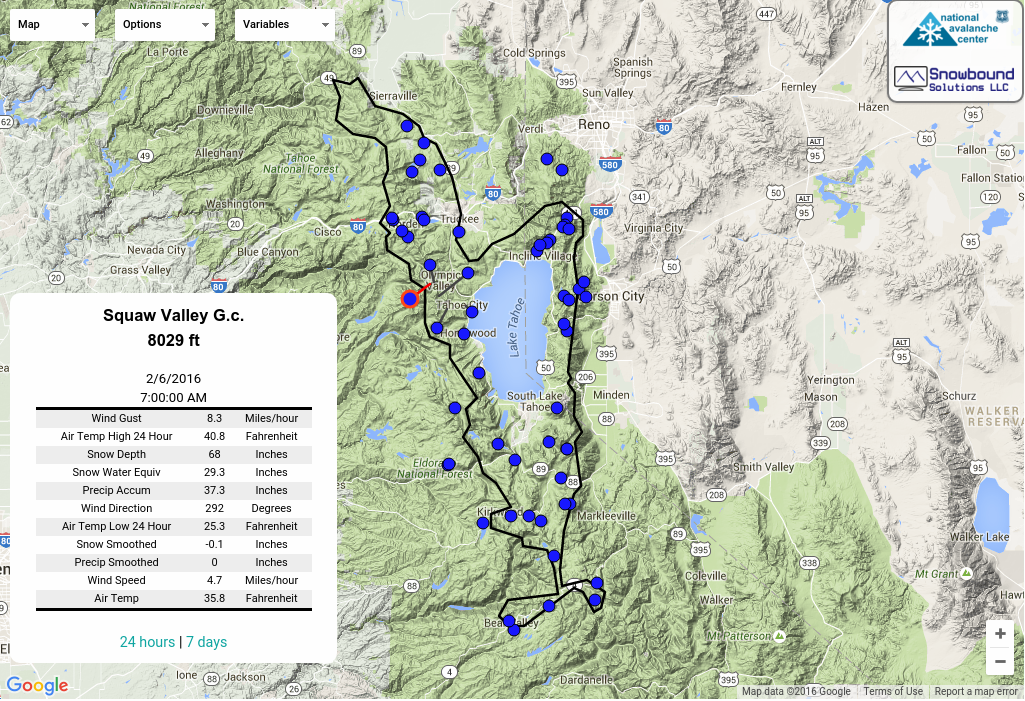

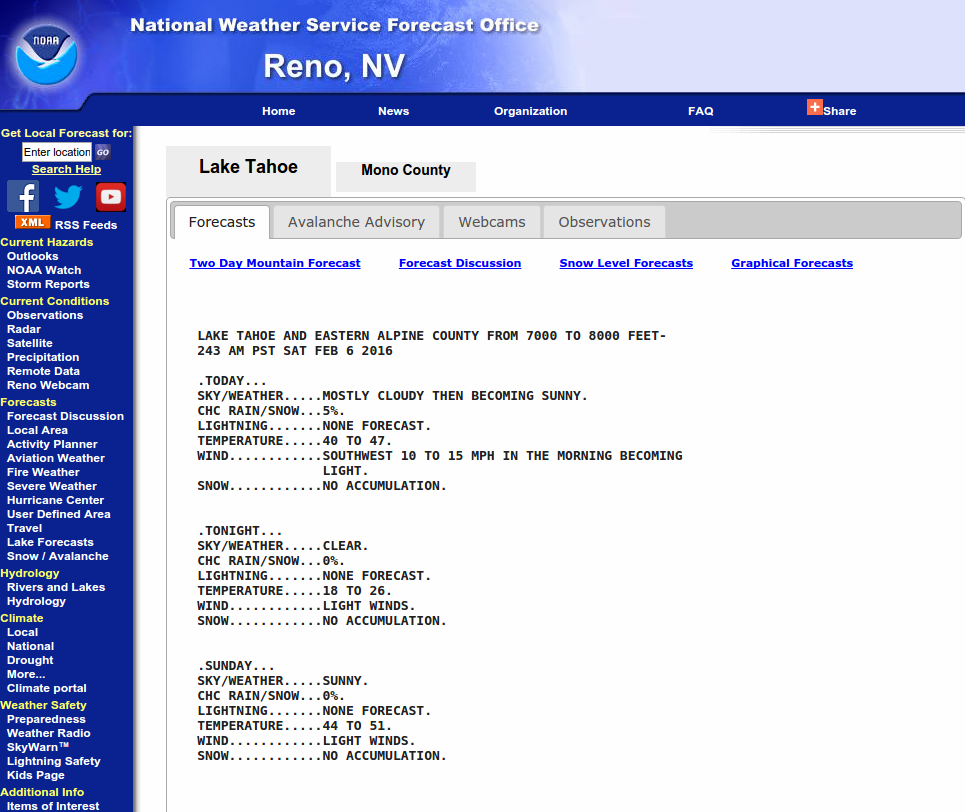

- Anticipate Conditions: Use the regional avalanche forecast and other resources to anticipate weather, snowpack, and avalanche conditions for the day.

- Create Safety Margins: Based on what you expect from your partners and conditions, create safety margins using terrain and timing. Allow room for error.

- Confirm Details: Evaluate options within your safety margins. Confirm details like your trailhead, start and return times, route options, and emergency gear.

- Stop to Talk: At the trailhead and then throughout the day, stop to talk about conditions, terrain, and group management.

- Manage Your Group: Use communication techniques and spacing and spotting techniques that are appropriate for the conditions and terrain.

- Maintain Awareness: As you travel, use the Conditions Alerts and Terrain Alerts checklists to maintain awareness. If you observe anything unexpected, stop your group.

- Debrief: At the end of the day, debrief what went well and what didn’t. Did you do it "right" or just get lucky?

- Submit Observations: Let the nearest avalanche center know what you observed, using language that you are comfortable with, and/or images and videos.